AdventureSmith Explorations’ Director of Sales & Operations, Justin Massoni, reviews his Sailing Indonesia: Jewels of Raja Ampat cruise aboard the 24-guest Ombak Putih. Read on for Justin’s review of his time exploring caves, swimming with stingless jellyfish and seeking out the famed bird-of-paradise.

An Introduction to Raja Ampat: The Four Kings

Indonesia’s Raja Ampat archipelago, meaning “four kings” in the language of Bahasa Indonesia, is a vast seascape comprised of more than 1,500 islands covering an area of 40,000 km² of land and sea. Located in the Coral Triangle, at the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Raja Ampat contains 75% of the world’s coral species and a wondrous array of flora and fauna, some found nowhere else on earth.

Well known to divers for years, Raja Ampat is just now being discovered by travelers that like to stick a little closer to the surface.

The four main islands (the “Kings”) of Raja Ampat are Waigeo, Batanta, Salawati and Misool, located just off the Birds Head Peninsula of Indonesia’s West Papua Province (the western half of Papua New Guinea). Well known to divers for years, this area is just now being discovered by travelers that like to stick a little closer to the surface. The expedition cruising season here is during the dry months in West Papua: November and December.

Recognizing the incredible importance of this marine environment, the Government of Raja Ampat Regency—in partnership with The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International and World Wildlife Fund Indonesia—embarked on an ambitious plan to establish seven Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) covering 9,100 km² within the archipelago. This is part of the larger Bird’s Head Seascape, a vast area of 183,000 km² that now contains 12 interconnected MPAs that aim to protect one of the planet’s most pristine marine environments, and a “coral nursery” to the world.

Ombak Putih Ship Review: “The White Wave”

My personal exploration of Raja Ampat began, as everyone’s must, in the port city of Sorong, West Papua, Indonesia. Sorong is the commercial capital of West Papua and boasts a host of business hotels. It’s a fine town to overnight in before your exploration of the true wonders that lie just offshore.

The pinisi motorsailer Ombak Putih—meaning “white wave” in Bahasa Indonesia—was to be my home for our exploration of Raja Ampat, and I cannot think of a more appropriate ship for the adventure of traveling from idyllic island to idyllic island, as the people of Indonesia have for centuries.

As we approached the ship at anchor in Sorong Harbor, a fresh ocean breeze immediately cut through the cloying coastal sultriness—as well as the stress that comes from traveling through any large city in Asia. Boarding Ombak Putih is a revelation; she is a gaff-rigged ketch just oozing with Indonesian charm and an Old World sense of simple luxury. These sturdy and efficient ironwood ships, built in the same way for hundreds of years on the islands surrounding Suluwesi, still serve as a main means of transport in Indonesia into the 21st century. Read a bit more about these pinisi ships on AdventureSmith’s blog.

The 24-guest Ombak Putih is a gaff-rigged ketch just oozing with Indonesian charm and an Old World sense of simple luxury.

Though we were only 12 for this journey, Ombak Putih can accommodate 24 guests in complete comfort and superb style. Her 12 cabins are a study in the efficient use of space aboard a ship—all boasting modern conveniences such as USB charging ports, air conditioning, stylish fixtures and ensuite bathrooms. The beach sarongs and towels, reusable water bottles and small daypack that await you on your berth make it clear that you won’t be spending much time inside peering through the brass porthole but rather out enjoying all that Raja Ampat has to offer.

One of the striking aspects of the pinisi ship-building style is the abundance of deck space. All passenger cabins are on the lower Cabin Deck. The Main and Top Decks are entirely devoted to crew quarters and public spaces. In these ships’ capacity as commercial vessels, the large open deck allows for the high stacking of light goods. In Ombak Putih’s capacity as a luxury passenger vessel, it allows for a spacious enclosed salon with room to relax and read, an expansive and modern galley, a charming outdoor dining area where all meals are served (completely covered in canvas to protect from sun and rain) and plenty of room for viewing wildlife and wild seascapes from the rail. On the Top Deck, covered viewing areas fore and aft of the wheelhouse provide an ample supply of benches, loungers, couches and even bean bag chairs for reading, napping, journaling, socializing with shipmates or simply watching the jaw-dropping landscapes of Raja Ampat slide by.

Anda dari mana? Crew, Guides, Friends

One of the great joys of travel is, of course, meeting people from cultures other than our own—celebrating our differences, our similarities and our shared experiences in the world. One of the things AdventureSmith Explorations pays very, very close attention to is the crew composition of our voyages. As a company of former guides, we recognize the supreme importance of cultural exchange, not just on scheduled excursions but at all times during your visit.

AdventureSmith’s trips encourage all travelers to befriend every member of the crew, and all crews are given the space to befriend our travelers.

One of the great advantages of our type of travel aboard small ships is that you often have, as your shipmates, denizens of the very region you are visiting. Our trips encourage all travelers to befriend every member of the crew, and all crews are given the space to befriend our travelers. Almost all of our adventures include explorations ashore that focus on cultural exchange. It is important to not lose sight of the fact that this same exchange happens every day aboard a ship. Your naturalist could be from Sulawesi, where she spent summers hiking in the highlands. Your snorkeling guide could be from Alor, where he learned to hold his breath for minutes on end while spear fishing as a child. Your chef could be from Bali, where he picked up a unique fusion of culinary traditions at a cultural crossroads. The deckhand that pilots your Zodiac with such an expert hand could have learned his trade growing up in the Kai Islands on the edge of the Banda Sea.

The people of the modern Republic of Indonesia represent myriad different traditions, and hail from 13,000 different islands in this vast archipelago. Our style of exploration gives the traveler an opportunity to connect to a place in a million different little ways, every day. This is one of the things that makes small ship travel such a rich way to experience the world. That steward you see every day at breakfast and exchange shy smiles? Next time ask him where he’s from: Anda dari mana?

Species Factory: Why Snorkeling Raja Ampat Rivals Scuba

Immediately after embarking Ombak Putih, the question on everyone’s lips was “when…do…we…get…in…this…water??” A measured “sooner than you think” was the reply. Within 30 minutes of weighing anchor, we were rejoicing as a pod of bottlenose dolphins frolicked in our bow wake. Within two hours we were snorkeling in 80-degree water above a pristine coral garden in a quiet cove, overhung with luxuriant jungle foliage.

As an avid scuba diver, I have experienced quite a few of the great undersea destinations of the world. I’ve spent weeks exploring the greatest of the New World coral ecosystems—the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef that extends from the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula to the Bay Islands of Honduras. I purchased a black-market visa at Eilat that allowed me to dive the Red Sea. I braved endless red tape and machine gun nests to dive three days in a row at Sipadan, off the north coast of Borneo in the South China Sea (eat your heart out divers). I spent an entire winter exploring the Sea of Cortez out of La Paz—an area called “the Aquarium of the World” by Jacques Cousteau. I’ve donned a drysuit, my thickest thermals and 40 pounds of lead to explore the icy depths off Kodiak Island in Alaska. None of it, none of it compares to the coral diversity and the sheer abundance of life I saw in Raja Ampat. And I didn’t even have to bribe a border guard, bundle up or struggle with complex equipment to do it.

The magic begins at four feet below the surface on these reefs.

I woke up every day and took a leisurely snorkel (or two or three) through magical coral gardens unlike any I had ever seen. Never once did I feel as if I was “missing out” by not donning dive gear. The magic begins at four feet below the surface on these reefs; all that is required is curiosity, a swimsuit and a sense of wonder for the myriad forms of life that compose the coral reef community.

A Strange & Wondrous Landscape: Snorkeling with Stingless Jellyfish

The islands of Raja Ampat are quite unlike many of the islands you find elsewhere in the world. They are comprised of ancient eroded limestone—karst formations, in the vernacular of geologists. This amazing topography is created by the dissolution of limestone formations when exposed to environmental forces such as wind and water, and is characterized by numerous caves and sinkholes.

We awoke one morning at anchor in Tomolol Bay, in giddy anticipation of being able to explore this landscape in a very unique way. We exited the Zodiacs at a massive sea cave entrance, snorkel gear in hand, for a truly memorable caving experience. Swimming through this eerily lit cavern from end to end took us 15 minutes, as most of my shipmates and I opted for a leisurely backstroke in order to marvel at the massive stalactite formations dripping from the cavern roof, 40 feet overhead. Our guide led the more adventurous of the group through the numerous pass-through “squeezes” that led from the main chamber and back, but many preferred to remain in the open and airy central cave chamber.

Emerging into the bright sunlight at the opposite entrance, my comrades and I laughed and shook hands, feeling a little like we had just visited another world together.

Strange and wondrous things can also happen to the creatures that inhabit the karst islets of Raja Ampat.

Strange and wondrous things can also happen to the creatures that inhabit the karst islets of Raja Ampat. Often these islets have an interior lake, much like the central lagoon in coral atolls. As these central lakes are separated from the surrounding sea water over millions of years, they sometimes come to support a large population of jellyfish that are able to survive in the now brackish waters. As none of their natural predators are able to inhabit such an environment, the resident jellyfish have no more need of their defensive stinging cells and have evolved over generations without them.

After a short skiff ride to a small islet and a steep ascent into the interior lake, my companions and I were treated to an amazing experience: snorkeling among these strange creatures. After some initial trepidation (we had experienced some of their stinging brethren the day before), the group was soon marveling at the surreal feeling of swimming slowly (and painlessly) through clouds of millions of spotted jellyfish.

Some of my shipmates later revealed that it was the strangest wildlife encounter they had ever experienced. “Trippy” was a term bandied about at dinner that night as we relived the day’s adventures over cold Bintang beers.

As with all other activities aboard Ombak Putih, no experience is necessary to snorkel. You need only a sense of adventure and a desire to explore the natural world in uniquely wonderful ways.

“Dearest Charles, I hope this letter finds you well.”

At AdventureSmith Explorations, we spend a lot of time in Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands, well known in large part due to the work of Mr. Charles Darwin. There’s the Charles Darwin Research Station, Darwin’s finches—even Darwin Island. There are statues of the guy everywhere.

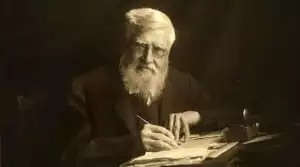

In this part of the world, the Welsh naturalist and explorer Alfred Russel Wallace looms large. Wallace spent the years 1854 to 1862 collecting and studying biological specimens in what was then called the Malay Archipelago (modern day Brunei, Singapore, East Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, East Timor and the western half of New Guinea). He came to Raja Ampat in 1860 to collect and study the area’s many birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae).

Though Wallace is experiencing a recent resurgence of interest, his contributions to our understanding of biogeography (the geographical distribution of species) and speciation through natural selection were largely eclipsed by his friend and contemporary Charles Darwin. It was actually a letter from Wallace in 1858 that prompted Darwin to finally publish his own theories on evolution that he had been developing ever since his visit to the Galapagos Islands aboard the HMS Beagle in the fall of 1835. A joint paper was presented to the Linnean Society later in 1858 (without Wallace’s knowledge, as he was still in Malaya) that introduced the theory of evolution to the world. Both men were credited with authorship of the paper, “On the Tendency of Species to Form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection.” But Charles Darwin’s connections and presence in England, as well as the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859 cemented his place in history as the father of the theory of evolution by natural selection.

Wallace is perhaps best known today for identifying the faunal boundary that runs between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi, and Bali and Lombok. The Wallace Line represents the boundary between distribution of Asiatic and Australian fauna species; animals to the west of this line are Asiatic and animals to the east are Australasian. The transitional zone that surrounds the line is known to biogeographers as “Wallacea.”

Upon returning to England in 1869, Wallace published one of the most readable of the Victorian travelogues, The Malay Archipelago, describing in vivid detail the people, plants and animals of this part of the world. For more on this book, see my recommended reading at the end of this post.

Better Luck Tomorrow, Wilson: Spotting a Bird-of-Paradise

One of the highlights of any trip to Raja Ampat is an opportunity to observe what Alfred Russel Wallace came to this region for: birds-of-paradise in the wild. The 39 species of bird-of-paradise are some of the most striking examples of evolutionary adaptation in the world. The island biogeography of these birds helped Wallace to formulate his theories of speciation, much like the finches of the Galapagos did for Charles Darwin.

After much referencing of the onboard bird guides and boisterous Bintang-fueled debate, we arrived at a consensus: We would seek out the Wilson’s bird-of-paradise.

The Wilson’s bird-of-paradise and the red bird-of-paradise are endemic to Raja Ampat—specifically to Waigeo and Batanta Islands. When our guide gathered us around the table one evening and informed us that we would have to choose which to visit the following morning, my shipmates and I were a bit perplexed. How do you choose between two of the most beautiful and rare birds on earth? What if you choose poorly? How are we to know which will be present in the forest on the appointed day, and which will not? Don’t worry she said. “You choose and we will find the birds.”

After much referencing of the onboard bird guides and boisterous Bintang-fueled debate, we arrived at a consensus: We would seek out the Wilson’s bird-of-paradise. The little bird just seemed too unreal. Can those vibrant colors really exist in nature, occupying the same six-inch space?

We rose in the calm dark of 3am next morning. After a quick breakfast and a gear check (closed-toed shoes, functioning flashlights, bug dope), we embarked the skiffs for the short ride to a small sandy beach backed with what looked to be impenetrable jungle. We all stood quietly for a while, just soaking up the stillness of the morning. Out of the darkness to seaward came an outrigger canoe and the two local gentlemen that were about to make this all possible.

“It seems as if Nature had taken precautions that these her choicest treasures should not be made too common, and thus be undervalued.” -Alfred Russel Wallace, on the pursuit of birds-of-paradise

The gentlemen were fishermen from a nearby village that maintain a rough trail into the forested hills and had constructed a simple blind from which to view the Wilson’s bird-of-paradise. The local community now has a vested interest in keeping this inland ecosystem intact; these little birds and the awestruck visitors they bring are now far more valuable to them than all the timber in the forest. We hiked in silence for an hour and arrived at the little blind just as the dark turned to grey dawn and the jungle truly came alive with sound. We waited breathlessly for the sounds that would indicate that the bird-of-paradise was about to begin his daily routine.

The male Wilson’s bird-of-paradise is an industrious little fellow, only about six inches tall. He creates and assiduously maintains a display court to attract the females of his species. The court is simply a patch of dirt on the forest floor, cleared daily of all detritus. Not a leaf or a twig remains after his morning cleaning routine. He then trills his call to attract females in the area who come to inspect his court, deciding if he has adequately displayed his fitness as a mate. If he succeeds—mating ensues. If not, well, there’s always tomorrow.

The most magical little bird I have ever seen lit up the forest floor not 15 feet from our blind…

The timing of our guides was impeccable. Within 10 minutes of our arrival, the Wilson’s song could be heard in the canopy overhead. Within 20, the most magical little bird I have ever seen lit up the forest floor not 15 feet from our blind and began his morning house cleaning, unconcerned by our presence.

Flitting from twig to twig, he heaved each out into the forest with a practiced flick of the head—trilling between lobs. As we held our collective breath and snapped photos in the low light, he heedlessly made ready for the day’s courting.

Sure enough, first one, and then two females appeared high in the periphery to survey his work. The female Wilson’s, as females in many species, don’t engage in garish color displays, instead opting for muted tones better suited to camouflage from predators. The two females were slightly larger and dun colored, but both had an iridescent blue cap similar to the male. Quite stunning in their own, rather more utilitarian, right.

We watched the display for perhaps 20 minutes, pulling for our little hero all the while. Both females at times would come down for closer inspection, sending him into a renewed flurry of cleaning up even the smallest imperfection in his court. Alas, first one, and then the other female departed, disappearing into the dense canopy.

When it was clear they weren’t coming back, he too moved on. Almost as one, those of us still in the blind muttered in sad chorus: “Better luck tomorrow, Wilson.”

The People of Raja Ampat

On our last afternoon, Ombak Putih anchored off idyllic Arborek Island—unique in that it is a palm-fringed sandy caye, and not limestone karst. The tiny island is home to Arborek Village and fewer than 200 souls. The subsistence fishing community here has created local regulations for the conservation of the surrounding reef in conjunction with international conservation groups. The success of their program is evident in the healthy and vibrant coral gardens we discovered, thriving even under and adjacent to the village pier.

As the sinking equatorial sun began to lengthen our shadows, we reluctantly left the water. Back aboard we washed of the salt and donned our best shorts and cleanest shirts for our evening in town with the people of Arborek.

Arriving again at the pier, we were met by what seemed like all the children that could possibly live in a village with a population of 200. Dressed in the mix of traditional and modern that is a hallmark of remote indigenous communities the world over, the group wore handmade grass skirts over threadbare board shorts and faded Real Madrid football jerseys adorned with beautiful seashell necklaces. The children had painted their legs, arms and faces with the white geometric designs favored by their ancestors that had braved the unknown to colonize these islands.

My companions and I were treated to the most wonderful traditional music and dancing right there at the end of the pier, the whole tableau painted with golden light from the fading sun.

In this world where commoditization of native traditions should be a concern for all travelers, the West Papuan community at Arborek felt real and vibrant, still connected to their revered past yet busily forging their own bright future.

Justin’s Suggested Reading for Indonesia Travel

At AdventureSmith Explorations, we encourage our travelers to arrive informed. Before each voyage, we provide travelers with reading lists related to their destination, covering everything from guidebooks to poetry. Whether you choose to read before, during or after your Indonesia trip—or perhaps all of the above—here is what I recommend:

The Annotated Malay Archipelago

by Alfred Russel Wallace

One of the great “gentleman scientist” travelogues and full of vivid detail on Indonesia’s people, plants and animals. It’s huge (about 800 pages); don’t be scared. Start at least a month before travel. It’s not a quick read, but it is truly worth the effort and contains amazing plates and illustrations. It was purportedly one of Joseph Conrad’s favorite books, and contained source material for Lord Jim.

Spice – The History of a Temptation

by Jack Turner

Another history of Europe’s hunger for spices that only grew on tiny islands in the area, and its impact on the region and the world.

A Brief History of Indonesia – Sultans, Spices and Tsunamis

by Tim Hannigan

Brings you up through the history of modern Indonesia: Suharto, East Timorese independence and the 2004 tsunami.

Nathaniel’s Nutmeg

by Giles Milton

A swashbuckling tale of the spice trade that defined an era of European exploration in Indonesia—and the tragic impact on the indigenous inhabitants of the region. You’ll never guess how the English came to possess the little island of “Manhattan,” halfway across the world.

For more photos from this trip, including a variety of coral and birds-of-paradise, view my Facebook album on AdventureSmith Explorations’ Facebook page.

This Indonesia cruise review was written by an AdventureSmith Explorations crew member. Read all AdventureSmith Expert Reviews for more trip reports. For dates, rates and booking information on this trip, see Sailing Indonesia: Jewels of Raja Ampat, or contact one of our Adventure Specialists to learn more about our small ship cruises and wilderness adventures: 1-800-728-2875.

Comments will be moderated and will appear after they have been approved.